If I got a nickel every time I read or wrote “encryption in transit” in system requirements, I would probably be the richest person on the planet. If you are a solution architect or developer, you probably see this requirement every day, and by now, even the average computer user knows that HTTPS is the standard way to securely exchange data on the internet. Somewhere in those whitepapers, requirements, or docs, there is always a TLS/SSL reference for secure service-to-service communication.

If you are a security expert or you already have a solid grasp of how this works, there is probably nothing new here for you. But if you are familiar with the term, use it daily, and never had a chance to do a proper deep dive, I recommend you stick around.

We will cover and explain concepts like PGP/GPG, symmetric vs. asymmetric keys, TLS/SSL, certificates, man-in-the-middle attacks, and the difference between public and private Certificate Authorities, when to choose one over the other, and what AWS, Azure, and Google Cloud provide so you don’t need to re-invent the wheel.

Let’s start with the basics.

PGP/GPG Encryption

PGP (Pretty Good Privacy) is a commercially available encryption tool. Its counterpart GPG, is an open-source, free implementation of the OpenPGP standard. Both use asymmetric encryption with a pair of private and public keys. The idea is simple but powerful. You keep your private key secret, while your public key can be shared with the world. Anyone can use your public key to encrypt a message, but only you can decrypt it with your private key. Remember that your private key should never be shared!

Give it or take, this is how most documents will describe it. What is a little less common is to find the explanation of what are these private and public keys in real life. Always remember that whenever we talk about encryption, there is always math involved. It can be more or less complex, but it always comes down to the calculation, despite numerous ways how the implementation may look alike.

Understanding Private and Public Keys

It’s time for a bedtime story!

First, we will solve the famous riddle, and then refine it to match the PGP encryption.

Imagine a time long ago when two castles needed to exchange secret messages without the courier being able to read them. The participants are John and Jane. Each of them owns a padlock and its matching key.

The courier cannot break the padlocks open, as he lacks the tools and time, so his only role is to carry a locked box back and forth between John and Jane.

Here is the problem: how can John and Jane exchange the message if neither has the other's private key, and they cannot simply hand over their own keys to the courier (because then he could unlock the box and read the contents)?

The solution is simple, though not immediately obvious!

- Jane prepares the box. She puts the message inside, locks it with her padlock, and keeps her key.

- The courier delivers this locked box to John.

- John adds his padlock. He cannot open Jane’s lock, but he adds his own padlock on the same box and sends it back.

- Jane removes her padlock.

- The box is still locked by John’s padlock, but Jane’s is now gone.

- The courier delivers the box back to John.

- John unlocks his padlock. Now John can open the box and read the message.

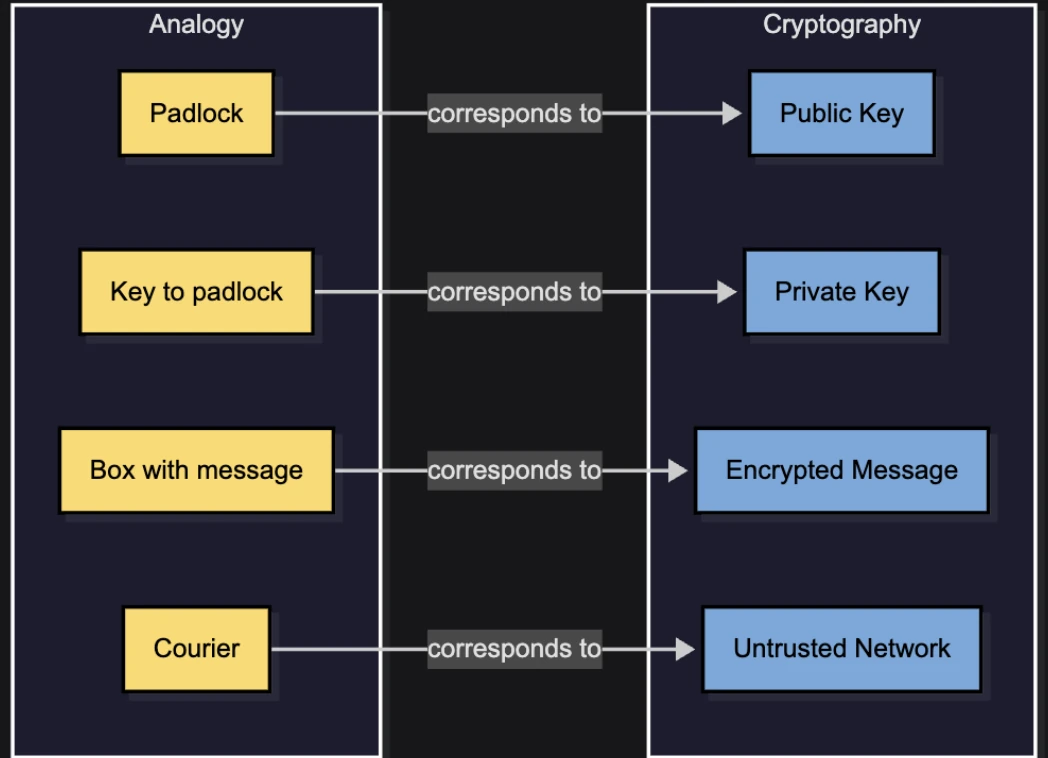

At no point did Jane or John share their private keys. Instead, the padlocks themselves acted like public keys. They were exchanged freely, while the keys to open them remained private. The courier, despite carrying the box multiple times, never had the ability to peek inside. We used “The Lock-and-Box Analogy” to describe Public-Key Encryption.

The more accurate, and probably simpler, way to describe it is that Jane has many padlocks that can be snapped shut without a key, but only a single key that can unlock any of them. The same goes for John.

In this version of the story, Jane sends one of her unlocked padlocks to John, and John does the same. When Jane wants to send a message, she locks the box with John’s padlock. This corresponds to encrypting with the recipient’s public key, because only John can unlock that padlock using his private key. The same rule applies in the opposite direction.

However, this introduces a major danger: trust! It’s not that John doesn’t trust Jane; the real problem is how he can trust the courier that the unlocked padlocks delivered to him truly came from Jane, and not from the courier himself (a man-in-the-middle).

Jane would need to “sign” her padlock somehow, and someone would need to confirm that the signature really belongs to her. So, what would be the analogy in the digital world?

Digital Certificates and Certificate Authorities (CA)

Welcome to the world of certificates, CA and their practical usage. We can think about the certificates as the ID document of the service, while the certificate authority is a service that is entitled and responsible for issuing and validating the certificates. In cyber security it is top priority to be sure that the entity we are exchanging the keys with is the one they are claiming to be. We mentioned that the encryption needed to prevent the eavesdroppers. The eavesdropper is a person that secretly listens to others' conversations to which they are not invited to. The encryption will prevent them from getting anything meaningful even if they find a way to listen.

However, there is another danger, and that is so-called “man-in-the-middle-attack”. In the previous parts, we had a courier that was delivering messages back and forth between John and Jane. When the padlocks were exchanged, if we don’t have a way to check the authenticity of the padlock, it can be replaced with the one from the attacker. So, this attack happens at a very early stage during the “handshake” and key exchange. The attacker's idea is to plant his own public keys to John and Jane, so whenever they lock the box, he would be able to unlock it with his own key, check the message, and then lock again with the recipient padlock so that there is nothing suspicious when the message is received at the real destination. Therefore, in order to preserve secure and secret communication, John and Jane must be sure that the padlocks are coming from the actual sender/recipient and not somebody else. They need to be uniquely signed and verifiable to remove any doubt about the padlock origin, eliminating the opportunity for man-in-the-middle to tamper with anything.

The certificate is a digitally signed ID Card that is binded to an entity that could be something like user, device, service, domain, or similar. We must have trusted certified authority that can issue these certificates and be able to verify their authenticity. There are many famous public certificate services that could be used on a public network. For example, the one common case is that we request from the CA to issue certificates that we will use to identify ourselves, so that clients sending requests to our domain can be sure that they are communicating with us, not with somebody else.

For example, when we are requesting certificates from the Amazon Certificate Manager to use with Route53, it will bind it to the domain, so when the user is visiting our website, their browser can ask for the certificate and verify the data provided to make sure that they are not visiting an imposter website which is usually malicious if they are claiming to be who they are not.

If the web browser cannot confirm the authenticity of the certificate with the authority, you will be warned that the connection is insecure, that the owner of the website may not be who they are representing themselves to be, and advised to leave the page or proceed at your own risk.

TLS and mTLS

TLS is a general-purpose protocol that provides encryption, integrity and authentication in internet communication. However, that is not its only purpose. TLS can secure lots of things, not just web, such as: SMTP, IMAP, gRPC, MQTT, DB connections… basically “anything over TCP”

Let’s start with the TLDR; version for a change:

- Certificates are digital IDs

- Certificate Authority is responsible for issuing certificates

- The certificates are used to confirm the authenticity of the parties involved into the data exchange

- This method of confirming authenticity is used in secure data transport (data in transit) in TLS.

- SSL and TLS are basically serving the same purpose except that the TLS is newer and de-facto standard nowadays.

- Transport Layer Protocol is used to encrypt and transport data between two servers or services.

If you are wondering how that works in practice, you can go back to the analogy from the very beginning. However, we will now describe, in technical terms, how it works end to end between sender and recipient. Before we do that, we have to mention one very important fact, which is the downside of asymmetric keys (private/public).

These keys are not suitable for large amounts of data. Encrypting and decrypting becomes more and more computationally expensive as the data size increases, so even with the right key, it can be a slow process to recover the actual data. Therefore, they are used primarily for authentication and key exchange, while the data is actually exchanged using symmetric keys.

- Sender and recipient establish contact (handshake).

- They exchange key-agreement parameters (typically ephemeral key shares) and derive the same symmetric key.

- A symmetric key is a single secret key that both sides share and use for both encryption and decryption.

- Symmetric encryption is much faster than asymmetric encryption.

- They must agree on the key securely. That is the reason why TLS uses asymmetric cryptography during the handshake.

- Once the symmetric key is derived, it becomes a session key in essence, which is then used to encrypt the real data.

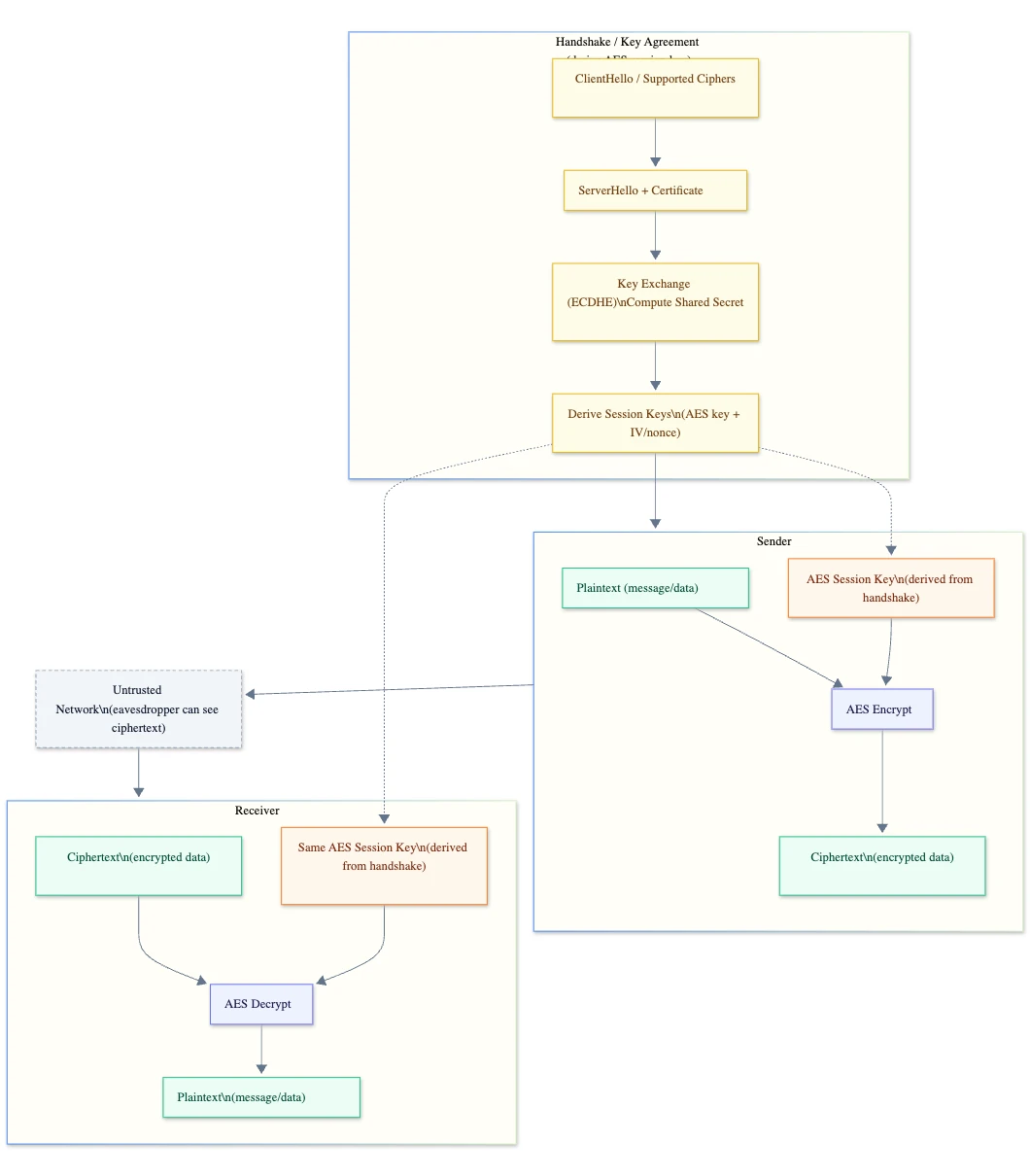

The handshake part consists of two major parts:

- Authentication

a. ClientHello part, where client starts, proposes TLS versions, sends a random value, and includes a key share for ECDHE.

b. ServerHello response, where the server picks the parameters and sends its certificate containing the server’s public key, signed by a CA.

c. Client verifies the certificate is:

i. signed by a trusted CA in the client’s trust store

ii. the cert is valid (expiry date, not revoked)

iii. the hostname matches

d. Server proves it owns the private key corresponding to the certificate by signing handshake data. This prevents a man-in-the-middle from impersonating the server with a copied certificate.

2. Key exchange

a. Client and server exchange their public keys.

b. Each side combines its own ephemeral private key with the other side's public key to compute the same shared secret. An eavesdropper can't compute it from public data alone.

c. They run that shared secret through a key derivation function to produce session keys resulting in both sides now having identical symmetric keys without ever sending those keys directly.

Let’s review the architectural diagram of the handshake part:

ECDHE stands for Elliptic Curve Diffie-Hellman Ephemeral.

- Elliptic Curve uses elliptic-curve math with smaller keys, fast and strong security.

- Diffie-Hellman is the key-exchange method that lets both sides derive the same shared secret.

- Ephemeral means that the keys are temporary for that session.

Exactly this “ephemeral” part is what gives TLS forward security. Forward security means if someone later steals the server’s private key, they still can’t decrypt old recorded sessions, because those sessions used throwaway keys.

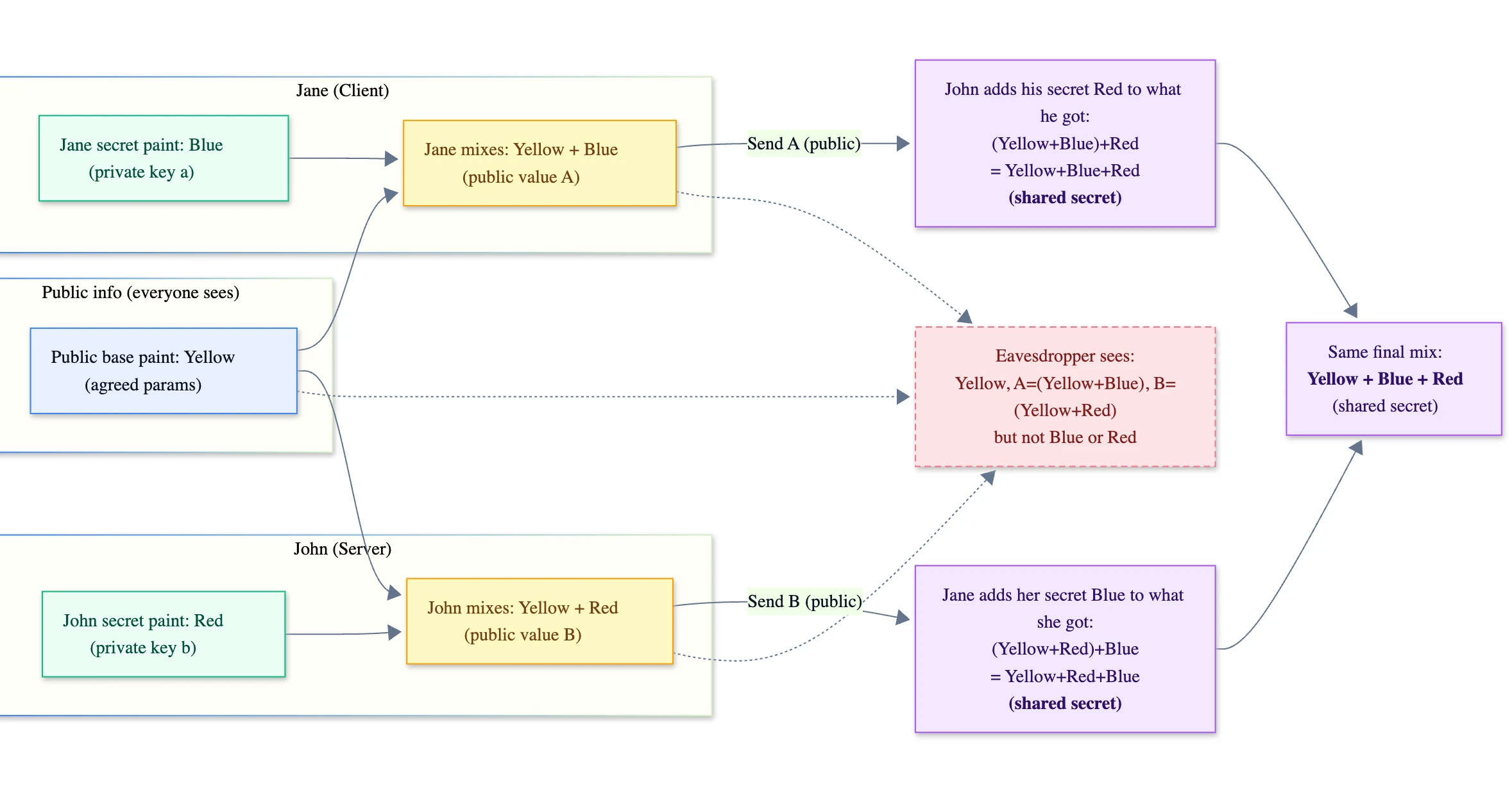

If you are wondering how it is possible that Jane’s public key + John’s private and John’s public key + Jane’s private key on the other side produces the same result, we can use very common mixing paint analogy for the somewhat complex math behind it,

Here is what is happening behind the scenes:

- John and Jane agree on a public paint color to be Yellow

- Jane chooses a secret color to be Blue (private key).

- John chooses a secret color to be Red (private key).

Mixing (calculation):

- Jane mixes Yellow + Blue and sends John the result (Jane’s public value).

- John mixes Yellow + Blue and sends Jane the result (John’s public value).

The Final Result:

- John takes what Jane sent and mixes his secret Red into it and now he has Yellow + Blue + Red

- Jane takes what John sent and mixes her secret Blue into it, and now she has Yellow + Red + Blue

- Both end up with the same final mix Yellow + Blue + Red, just added in different order, but the math operation is commutative so the order doesn’t matter.

An eavesdropper only sees:

- Yellow (public parameters)

- Yellow + Blue (Jane’s public value)

- Yellow + Red (John’s public value)

- but without knowing Blue or Red, they can’t recreate the final mix.

After the handshake procedure, client and server start using symmetric keys to encrypt the data being exchanged.

Finally, it’s good to mention that mTLS (mutual TLS) is just a server requesting from the Client to authenticate to the server in the same way the server authenticates to the client.

Why RSA is Becoming Obsolete

RSA encryption, and especially decryption, is computationally heavy. Its security is based on the difficulty of factoring the product of two large prime numbers. With today's classical computers, factoring a 2048-bit number would take millions of years. However, RSA does not scale well. As computing power increases, key sizes must also increase, which quickly becomes inefficient.

RSA also isn't suitable for encrypting large files. In practice, it can only handle data roughly up to the size of the key. That is why it is mostly used to encrypt session keys or small pieces of data, rather than full documents.

Shor's Algorithm, a quantum algorithm for factoring large numbers, has been known since 1994, but until now classical hardware wasn't powerful enough to make it relevant. As quantum computing advances, this threat is becoming real. With sufficient quantum resources, RSA encryption could be broken in a matter of hours or even minutes, regardless of key size.

Cryptocurrency and Cryptography in Quantum Era

In theory, "harvest now, decrypt later" is a problem for crypto, but only in some cases. For example, Bitcoin addresses in a wallet are safe if they have not been used. By "used" I refer to transactions from that address in a wallet, meaning that the public key has not been exposed. Somebody can harvest the public key from the transaction (because it is public, obviously) and then, when they have enough quantum power, derive the private key from it. Today this would require millions of years, but with quantum computing achieving enough power, it could become a matter of minutes or hours.

However, we are still 15–20 years away from this possibility. The migration is already underway to post-quantum algorithms that protect against quantum attacks. So, if the address has been revealed by a transaction and it is not migrated into a new wallet, there is a possibility that in 15–20 years, somebody who has harvested the public key now could be able to unlock the target wallet. To do that, they would need a few million qubits, and those must be error-corrected qubits, not just physical ones. Currently, quantum computers operate with fewer than 100 error-corrected qubits, even though we have passed the 1,000 physical qubit mark. Theoretical threats may become concerning after 2040.

What To Use Today

The practical answer is hybrid encryption. Until post-quantum algorithms are fully standardized and widely deployed, continue using RSA (or ECC) for key exchange, while relying on symmetric algorithms like AES for actual data encryption. AES remains strong even against quantum threats. It only requires larger key sizes to stay secure.

There is no need to panic today. RSA is not "broken" yet, at least not that we are aware about, but organizations like NIST have already announced plans to deprecate RSA and elliptic-curve cryptography (ECC) by the early 2030s, replacing them with post-quantum algorithms.

The main takeaway, beyond moving away from RSA, is the importance of following best practices and trusted sources in technology.

HTTPS

Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP) uses a client–server model. The client sends requests to a server, and the server returns a response that includes a status code, metadata, and optional data. The most common use of HTTP is web browsing.

HTTPS is simply HTTP with an added security layer provided by Transport Layer Security (TLS). TLS encrypts the connection and protects the data in transit.

HTTPS = HTTP + TLS.

Private Certificate Authority (PCA)

Now that we know how to authenticate our server and provide secure data exchange, there is only one question left to be answered. What is Private CA and why do we need one, as there are many trusted Public CA we can use. Well, yes and no, not really, at least not when we have an isolated private network.

The first problem with the publicly issued certificates is that they do not support private DNS domains. They only support what is publicly available over the internet. For example, we cannot use public CA to sign the company.local domain that we decided to use internally in our VPC on AWS cloud for example, instead of using long API Gateway or Cloud Front URL.

Even though our private network is isolated from the outside world, that does not mean we do not have to implement security best practices which also includes end-to-end encryption between local services. Neglecting best practices and security due to overtrusting our network isolation may become a fatal error, so better be safe than sorry.

Then, how do we do this? Exactly the same way we do it on a public network, except we need to introduce trusted private certificate authority PCA. What could be a use case for the certificates issued by the PCA in a private network?

We want to be sure when our services are communicating with each other to be sure that the communication is conducted with the intended entity, and also we want to have end-to-end encryption like it is a public network. This way we are reducing the blast radius in case of breach. Even though we are in a private network, it does not mean that there is no real danger. It takes only a single compromised instance, bad security group, VPC misconfig, or similar oversight, to open our network for the attacker to commence various types of attacks if the data isn’t protected in transit and storage.

Since we are cloud oriented it’s time to visit the usual suspects such as AWS, Azure, and GCloud to see what they have to offer, so we don’t have to re-invent the wheel when it comes to issuing certificates.

AWS Demo

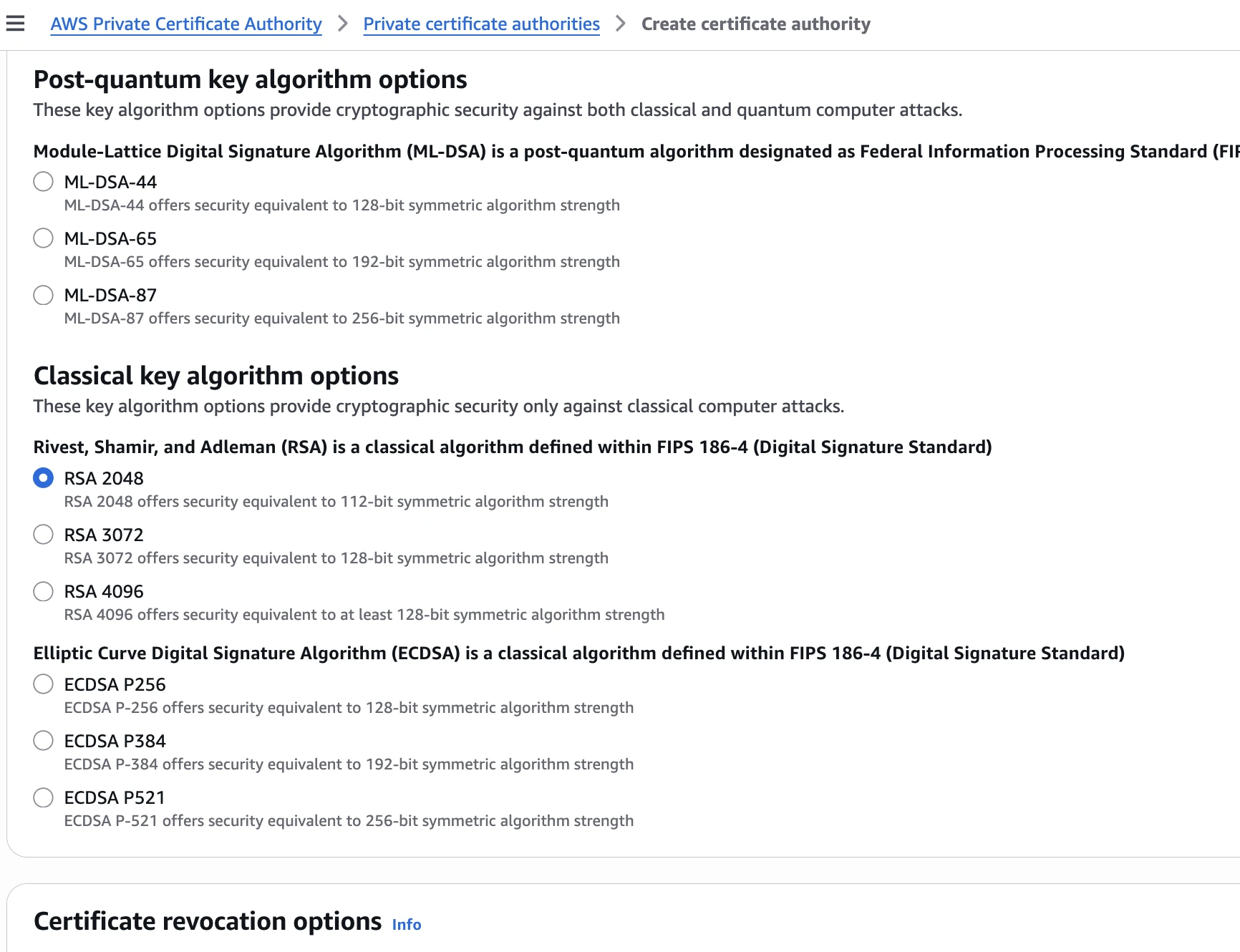

AWS Private Certificate Authority works great in combination with AWS Certificate Manager. We need to set up a PCA in order to issue certificates that we can store in ACM and use them as needed. There are plenty of options available, and even to choose a quantum era ready algorithm.

Suppose our company domain name is https://secrets.guru. We want our local services to work under the https://hq.secrets.guru local domain, which is accessible only within the internal VPC.

- Set environment variables

REGION="us-east-1"

CA_COMMON_NAME="Secrets Guru Root CA"

IDEMPOTENCY_TOKEN="$(date +%s)"

2. Create Root JSON file

cat > ca-config.json <<'JSON'

{

"KeyAlgorithm": "RSA_4096",

"SigningAlgorithm": "SHA512WITHRSA",

"Subject": {

"Country": "BA",

"Organization": "Example",

"OrganizationalUnit": "Platform",

"State": "Sarajevo",

"Locality": "Sarajevo",

"CommonName": "Example Root CA"

}

}

JSON 3. Create Certificate Authority CA

CA_ARN="$(aws acm-pca create-certificate-authority \

--region "$REGION" \

--certificate-authority-type ROOT \

--certificate-authority-configuration file://ca-config.json \

--idempotency-token "$IDEMPOTENCY_TOKEN" \

--query 'CertificateAuthorityArn' --output text)" 4. Get the CA CSR

aws acm-pca get-certificate-authority-csr \

--region "$REGION" \

--certificate-authority-arn "$CA_ARN" \

--output text > ca.csr.pem 5. Issue the self-signed root CA certificate

CERT_ARN="$(aws acm-pca issue-certificate \

--region "$REGION" \

--certificate-authority-arn "$CA_ARN" \

--csr file://ca.csr.pem \

--signing-algorithm SHA512WITHRSA \

--template-arn arn:aws:acm-pca:::template/RootCACertificate/V1 \

--validity Value=10,Type=YEARS \

--query 'CertificateArn' --output text)" 6. Retrieve the issued certificate

aws acm-pca get-certificate \

--region "$REGION" \

--certificate-authority-arn "$CA_ARN" \

--certificate-arn "$CERT_ARN" \

--query 'Certificate' --output text > ca-cert.pem 7. Only a self-signed cert can be imported as a root CA

aws acm-pca import-certificate-authority-certificate \

--region "$REGION" \

--certificate-authority-arn "$CA_ARN" \

--certificate file://ca-cert.pem 8. Verify

aws acm-pca describe-certificate-authority \

--region "$REGION" \

--certificate-authority-arn "$CA_ARN" \

--query 'CertificateAuthority.Status' --output text 9. Finally, we allow ACM to issue or renew ACM-managed private certs from PCA.

aws acm-pca create-permission \

--region "$REGION" \

--certificate-authority-arn "$CA_ARN" \

--principal acm.amazonaws.com \

--actions IssueCertificate GetCertificate ListPermissions 10. Request private certificate for the hq.secrets.guru

CERT_ARN="$(aws acm request-certificate \

--region "$REGION" \

--domain-name hq.secrets.guru \

--certificate-authority-arn "$CA_ARN" \

--query CertificateArn --output text)" 11. Wait until it is issued

aws acm wait certificate-issued --region "$REGION" --certificate-arn "$CERT_ARN"12. Attach the certificate to the ALB https listener

ALB_ARN="arn:aws:elasticloadbalancing:...:loadbalancer/app/..."

TG_ARN="arn:aws:elasticloadbalancing:...:targetgroup/..."

aws elbv2 create-listener \

--region "$REGION" \

--load-balancer-arn "$ALB_ARN" \

--protocol HTTPS \

--port 443 \

--certificates CertificateArn="$CERT_ARN" \

--default-actions Type=forward,TargetGroupArn="$TG_ARN"

13. AWS explicitly notes that private-CA certs aren’t trusted by default. That is why we must install the CA certificate into our client trust stores. For the demo purposes we are using our client machine, so depending on the underlying OS, we can do something like:

a. curl

curl --cacert root-ca.pem https://hq.secrets.gurub. MacOS

add root-ca.pem to Keychain as a trusted rootc. Linux - drop it into system CA bundle (update-ca-certificates / update-ca-trust)

d. Windows - import into “Trusted Root Certification Authorities”

Google Cloud Demo

Google Cloud has a very similar services to offer. Here is the solution for the same scenario using the CLI.

- Public company domain:

secrets.guru - Internal-only service DNS:

hq.secrets.guru(resolves only inside a VPC) - Issue a private TLS certificate for

hq.secrets.gurufrom a private ****Root ****CA - Store/deploy certificate using Certificate Manager

- Attach to an HTTPS load balancer target proxy (GCP equivalent of “attach to ALB listener”)

1. Set environment variables

PROJECT_ID="$(gcloud config get-value project)"

REGION="us-east1"

POOL_ID="secrets-guru-pool"

ROOT_CA_ID="secrets-guru-root-ca"

DOMAIN="hq.secrets.guru"

ROOT_CA_PEM="./root-ca.pem"

LEAF_CERT_PEM="./hq.secrets.guru.cert.pem"

LEAF_KEY_PEM="./hq.secrets.guru.key.pem"

CM_CERT_NAME="hq-secrets-guru-selfmanaged"

CM_MAP_NAME="hq-secrets-guru-map"

CM_ENTRY_NAME="hq-secrets-guru-entry"2. Enable APIs

gcloud services enable \

privateca.googleapis.com \

certificatemanager.googleapis.com \

dns.googleapis.com \

compute.googleapis.com3. Issue the private leaf certificate for hq.secrets.guru

gcloud privateca certificates create "hq-secrets-guru-leaf" \

--issuer-pool "$POOL_ID" \

--issuer-location "$REGION" \

--dns-san "$DOMAIN" \

--subject "CN=$DOMAIN, O=Example, OU=Platform, C=BA" \

--use-preset-profile "leaf_server_tls" \

--validity "P365D" \

--generate-key \

--key-output-file "$LEAF_KEY_PEM" \

--cert-output-file "$LEAF_CERT_PEM"4. Store the certifacate in Certificate Manager

gcloud certificate-manager certificates create "$CM_CERT_NAME" \

--location="global" \

--certificate-file="$LEAF_CERT_PEM" \

--private-key-file="$LEAF_KEY_PEM"5. Attach the certificate to the HTTPS load balancer (target proxy)

gcloud certificate-manager maps create "$CM_MAP_NAME" --location="global"

gcloud certificate-manager maps entries create "$CM_ENTRY_NAME" \

--location="global" \

--map="$CM_MAP_NAME" \

--hostname="$DOMAIN" \

--certificates="$CM_CERT_NAME"

PROXY_NAME="TARGET_HTTPS_PROXY"

gcloud compute target-https-proxies update "$PROXY_NAME" \

--certificate-map="$CM_MAP_NAME"6. Private DNS for hq.secrets.guru (VPC-only)

ZONE_NAME="secrets-guru-private"

VPC_NETWORK="default" # change

LB_IP="10.10.20.30" # change (internal LB IP)

gcloud dns managed-zones create "$ZONE_NAME" \

--dns-name="secrets.guru." \

--visibility="private" \

--networks="$VPC_NETWORK"

gcloud dns record-sets transaction start --zone="$ZONE_NAME"

gcloud dns record-sets transaction add "$LB_IP" \

--name="$DOMAIN." \

--ttl="300" \

--type="A" \

--zone="$ZONE_NAME"

gcloud dns record-sets transaction execute --zone="$ZONE_NAME"7. Trust the private CA on clients

curl --cacert "$ROOT_CA_PEM" "https://hq.secrets.guru"The main difference is that in AWS PCA we explicitly get CSR, then issue root cert, then import it.In CAS, creating the root CA is more “managed”. We create the root in the pool and then issue leaf certs. Also the deployment is not “listener” based. It is typically target HTTPS proxy with certificate map.

Azure Demo

To achieve the same thing with Azure, there is a slight issue. There is no 1:1 service that corresponds to AWS or Google Private certificate authority, but that will not be a deal breaker. We can still host our own PCA.

- Public domain:

secrets.guru - Internal-only name:

hq.secrets.gururesolves only inside VNet - TLS terminated on internal Application Gateway

- Cert issued by private CA ****hosted in Azure

- Create Private DNS zone

secrets.guruand link it to the VNet - Create an

Arecord forhq.secrets.gurupointing to your internal App Gateway private IP - Create a private CA which is Azure-side equivalent of PCA

a. Deploy AD CS on a VM, and create a Root CA

b. Issue a server certificate for hq.secrets.guru from that CA

4. Import issued certificate into the Azure Key Vault Certificates.

5. Attach certificate to the internal HTTPS endpoint and configure Azure Application Gateway v2 with an HTTPS listener that pulls the server certificate from Key Vault

6. Resolve client trust issues same as with AWS and GCloud because the cert chains to private CA, clients won’t trust it by default, by distributing the Root CA certificate into client trust stores.

Establishing Trust Between Azure and AWS service (mTLS)

It doesn’t matter in which direction our application communicates, establishing trust between services follows the same principle. If we want an Azure service to access resources in an AWS account, we first need to establish trust between the two sides. On top of that, we need Transport Layer Security (TLS) to make that data in transit can’t be read or tampered with.

In this example, we use mutual TLS (mTLS). The client presents a certificate signed by our private Certificate Authority, and the server does the same. During the TLS handshake, both sides validate each other’s certificates, which means both endpoints are authenticated and can begin exchanging encrypted data.

openssl genrsa -out client.key 2048

openssl req -new -key client.key -out client.csr -subj "/CN=azure-function-name"This creates client.key , a private key, and client.csr , client signing request that contains public key and private key, which we can then use to issue certificate from our private certificate authority.

➜ REGION="us-east-1"

➜ CA_ARN="arn:aws:acm-pca:REGION:ACCOUNT:certificate-authority/RANDOM_GUID"

➜ CERT_ARN=$(aws acm-pca issue-certificate \

--region $REGION \

--certificate-authority-arn "$CA_ARN" \

--csr fileb://client.csr \

--signing-algorithm "SHA256WITHRSA" \

--validity Value=30,Type=DAYS \

--output text --query CertificateArn)After issuing the certificate, we can finally retrieve the issued certificate and chain:

➜ aws acm-pca get-certificate \

--region $REGION \

--certificate-authority-arn $CA_ARN \

--certificate-arn $CERT_ARN \

--query Certificate --output text > client.crt.pem

➜ aws acm-pca get-certificate \

--region $REGION \

--certificate-authority-arn $CA_ARN \

--certificate-arn $CERT_ARN \

--query CertificateChain --output text > client.chain.pemNow we create PFX files:

cat client.crt.pem client.chain.pem > client.fullchain.pem

openssl pkcs12 -export -out client.pfx -inkey client.key -in client.fullchain.pem

base64 -w0 client.pfx > client.pfx.b64Then we need to set app settings to reference these values from the key vault, instead directly their content.

CLIENT_CERT_PFX_BASE64= contents ofclient.pfx.b64CLIENT_CERT_PFX_PASSWORD= your PFX password

The full source code of the demo is available on the GitHub.

The Terraform/OpenTofu demo project builds a full private cross-cloud path with the mTLS. The project is fully tested and ready to be deployed. Check the readme file for the instructions.

Also get familiar with the https module in NodeJS documentation, especially the request options part.

The project contains:

- Azure Function (Linux, Node) inside an Azure VNet

- Site-to-site VPN: Azure VPN Gateway <-> AWS VPC (VGW)

- Azure DNS Private Resolver forwards

secrets.guruqueries to AWS Route 53 Resolver inbound endpoint (Note that secrets.guru does not exist, it is not registered publicly, only resolves locally. You can put anything there, i.e. mysuperdomain.local). - AWS internal ALB (HTTPS) with:

- Server certificate issued by AWS Private CA (ACM private certificate)

- mTLS verify using an ALB Trust Store (CA bundle in S3)

- ECS Fargate service behind ALB returning "hello world" and logging client certification subject so we can confirm mutual Transport Layer Security.

.png)

After the deployment, you will see a lot of useful outputs:

Outputs:

alb_internal_dns_name = "internal-xxxxxxx.us-east-1.elb.amazonaws.com"

aws_route53_inbound_resolver_ips = [

"10.x.x.x",

"10.x.x.x",

]

aws_vpc_id = "vpc-xxxxxx"

aws_vpn_tunnel1_outside_ip = "x.x.x.x"

azure_function_app_name = "kvrep-xxxxxx-func"

azure_key_vault_name = "kvrepxxxxxx"

azure_key_vault_uri = "https://xxxxxx.vault.azure.net/"

azure_resource_group = "kvrep-rg-xxxxx"

azure_vpn_gateway_public_ip = "x.x.x.x"

route53_private_zone_id = "xxxxxxxxxxx"

service_fqdn = "api.secrets.guru"This is how we can test the azure function.

az functionapp function invoke \

--resource-group <our-rg> \

--name <our-function-app-name> \

--function-name hello \

--method GETKeep in mind that there are a lot of resources here that will cost you money. If you are deploying it only for the demo purposes, then make sure you destroy it after you are done:

tofu destroyOn the other hand if you are doing production setup, the only thing you are missing is to enable both tunnels in your VPN Customer Gateway. You will receive a lot of warnings from AWS if you don’t do it, similar to this:

Important notice about your AWS Account regarding VPN connections [AWS Account: 123456789012]

View details in service console

Hello AWS VPN Customer,

You're receiving this message because you have at least one VPN Connection in the us-east-1 Region, for which your VPN Customer Gateway is not using both tunnels. This mode of operation is not recommended as you may experience connectivity issues if your active tunnel fails.

The VPN Connection(s) which do not currently have both tunnels established are:

vpn-03049b26658e98f4f

Final Thoughts

With that, we can close this chapter. The main takeaway, beyond moving away from RSA, is the importance of following best practices across every aspect of security, no matter which platform you prefer. When it comes to security, trade-offs and compromises are not an option, so we need to stick to, and firmly uphold, the highest standards.

Certificates are what make end-to-end encryption scalable. They bind identities to public keys, so we can authenticate who we are talking to before any secrets are exchanged. Once trust is established, the handshake provides short-lived session keys, and symmetric encryption protects the real data efficiently. We have covered confidentiality for the data in transit, integrity against tampering, and assurance that the service on the other end is the one it claims to be. This is what end-to-end encryption is build upon.

%20(1).svg)

.svg)